The Mongol Empire and its Influence 1218-1747: from mass terror to urban administrators

For the history of the Central Asian steppe peoples prior to the rise of the Mongols in the 12th century, see René Grousset, The Empire of the Steppes (1970), and Barthold, Turkestan down to the Mongol invasion (1968) and Svat Soucek, A history of Inner Asia (2000). A short review chapter this period is Edmund Bowsworth (2010). Among the better survey articles on the rise of the Mongol Empire to its successor dynasties and kingdoms, is Beatrice Manz’s essay in the The New Cambridge History of Islam (Vol. 3, 2010). A discussion of the Timurid Dynasty and Empire as a successor to the Mongol Empire is found in Maria Subtelny (Subtleny 2010).

The origins of the Mongols are shrouded in the myth of its founding emperor Temüjin (1167-1227 C.E.), better known as Chinggis Khan (the new spelling) or Genghis Khan under the better known but older transliterated spelling of this name. Temüjin’s extraordinary rise and success places him among the most fearsome but successful conquerors of world history. The lasting influence of the Mongol Empire’s form of organization and its Turkic and Mongolian ethnic influence is seen in the survival of the Chingissid Dynasty and culture that survived in Central Asia well intot he sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (McChesney 2010).

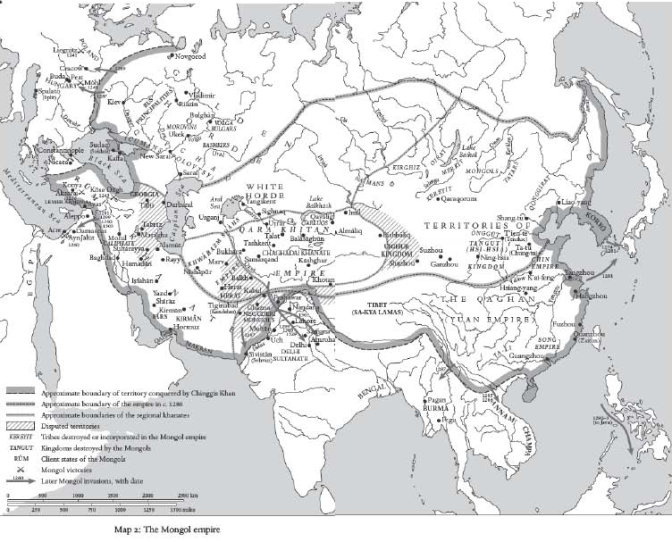

The Mongolians were successor nomadic rulers to several adjoining nomadic dynasties. To their West the Qara Khitay were a powerful rival tribe that ruled in the areas adjoining the Islamic territories of Western Central Asia near Samarkand. The Mongols also bordered the area of the Tü-Chüeh Turkic empire that dominated the eastern steppe in the 6th to 8th centuries[1]. This was succeeded by the Uighur kingdoms that bordered the Mongols to their South and West. Their home territory was in the eastern and northern half of the Central Asian grassy steppe lands, south and east of Lake Baikal (see Map 2). Most of the Mongol tribes were nomadic pastoralists who raised their horses and other livestock on the grasslands, while some were living in forested areas where they hunted and fished; some Mongol communities also were farmers. Like most nomadic societies it was a tribal society where kinship either real or imagined played important roles in maintaining or forming alliances to hold power and cooperation between groups and tribes. The Uighurs had developed their own script that influenced or was incorporated into a unique Mongolian writing system that was used in its early dynastic period.

The rise of Temüjin (Chinggis Khan) is legendary and partly myth. The Secret History of the Mongols, whose text was preserved and translated from Chinese, provides the mythical legend of his family, that is comparable in purpose with the mythical origin of Romulus and the founding of Rome. Few details are known other than he had been forced out of his own tribal component, the Kiyran-Borjigin section of the Mongol peoples. Tatar forces had attacked and defeated his tribe in about 1147, a generation before he was born, and he was partly orphaned at the age of eight when his father was killed by Tatars. It seems his mother was then outcaste, and she was forced to raise her sons from outside her own tribe. This appears to have had an enormous influence on Temüjin’s upbringing for he learned to make new allegiances with the Keraits, an outlying tribe and when he grew old enough he returned to claim his bride. He gained the trust of the Keraits whose leader To’oril (Ong Khan) had been an ally of Temüjin’s father. Both men were forced to flee under pressure from the central Mongolian tribes and each fled in different directions. Ong Khan sought and received support from the Qara Khitay in the West, while Temüjin apparently sought safety in exile in China. According to the classic primary source and account of this history, The Secret History of the Mongols, Ong Khan managed to regain control of his tribe with Temüjin’s assistance in about 1196, (Ch. V, 85-89) who as a reward was adopted and made the heir to his chieftainship. In the Secret History we read of Chinggis Khan’s serious wounds in battle and close calls, all adding to his legendary leadership (Ch. IV, p. 74). But thereafter both fell out with each other and when Ong Khan was killed in raids by the rival Naiman, Temüjin consolidated his new power, organizing a powerful military bureaucracy and reward system for his soldiers with whom he shared some power and tasks. Taking his new title, Chinggis Khan, Temüjin was ready to establish an empire of conquest and expansion, first to the West and then toward China[2].

By 1207-1218, Temüjin’s frontier armies had pursued out the Qara Khitay and pushed on toward the Islamic dynasties in Central Asia. By 1219 his immense armies, using swift maneuvers, deadly archery and a systematic decimal system of regimental organization had defeated the Khwārazm Shah and cleared the way for an invasion of the Transoxiana cities of Bukhara and Samarkand. The Mongols invoked terror methods of sheer intimidation. They also carried with them skilled engineers who made siege engines and batteries that bashed in walls and towers. When cities like Bukhara and Samarkand resisted, they were laid siege, that collapsed after only a few days. A systematic butchering of the entire military armies of these cities followed, while Bukhara, the city that had raised the great physician and philosopher Ibn Sina in the late 10th century, was burned to the ground and its civilian population removed either for slavery, forced labor or execution. The strategy was to force neighboring cities to capitulate and surrender without any resistance, which some did. After their surrender those cities were immediately placed under Mongol administration and a strict system of taxation[3].

By 1220 the Mongols had reached Khurāsān and as far as Transcaucasia in modern day Georgia. Meanwhile, another large force of the Mongols had pushed south into Persia and trapped and forced into exile the last effective ruler of Khwārazm Shah’s, his son Jalā al-Dīn who was forced to flee into exile by crossing a river in a desperate attempt to escape the Mongols. Over the next year Chinggis Khan had to consolidate his holdings in the West as a series of rebellions broke out in Afghanistan and Persia. Parts of Persia would resist and rebel against Mongol rule into the 1230s when Jalāl al-Dīn was killed by Kurds in 1232. Parts of Georgia and Armenia also offered some resistance. Thereafter, Chinggis Khan returned to the East and began his invasion of China until his death in 1227 (The Secret History, Ch. XII, 209). Upon his death this empire was divided to be ruled by his four sons of his first wife; these were Jochi and Chaghadi, Ogedei and Tolui, Ogedai was charged as the main military Khan and directed both the Western Campaigns into Transoxiana and invasions of Korea and China, while Jochi and his sons took control of portions of Russia.

To gain revenues the Mongolian state controlled monopolies of salt, wine, beer and other liquor, as well as on yeast. They further extended taxes on households and on trade[4]. Not all was evenhanded in this expansive empire. Ogedai, as with many other Mongol military men was an alcoholic, for there was a cult and addiction to massive amounts of imbibing in the various forms of alcohol that the empire gained, rice wine from China and Southeast Asia, beer from the West, and grape wine and other alcoholic beverages that were brewed and consumed. When Ogedai died of alcoholism his wife administered some of the state as a regent and the Mongol command was not reconsolidated until Möngke Khan’s installment on the throne in 1251. While Möngke’s reign was marked by internal purges within the Mongolian elite clans, particularly against the purged supporters of Ogedai’s line, Möngke was a competent administrator who instituted a progressive tax in Iran, in which the wealthy might pay a rate seven times more than the poor. He also instituted the system of a census in his new Chinese territories[5].

Möngke also sent his two younger brothers to lead new invasions of expansion. He sent Qubilai Khan, who is mentioned in Marco Polo’s journals, to rule in China, while he sent Hülegu to rule in the Western Central and South Asian territories. By 1258 Hülegu had sacked Baghdad and continued on to invade Syria where he sacked Aleppo. Thereafter, other Syian cities, including Homs and Damascus surrendered without a fight to spare themselves from massacre. The physical limits of Hülegu’s conquest were tested at the famous battle of Ayn Jālūt in Palestine, where his frontier forces were defeated by a combined force of Egyptian and Syrian Mamluks Thereafter the Mongols lost hegemony over Syria, which was still in the throes of Crusader wars and divisions.

In the West, as the Mongols retreated from Syria back toward Iraq and Persia they established the Ilkhanid dynasty, while the Mamluks gained power in Egypt and Seljuks in Syria and where some Christian Crusader city-states endured as at Acre. The Ilkhanids absorbed Persian language and culture in its administration. Two of the earliest histories of the Mongols were written by Persian administrators who worked for the Ilkhanid state. These were Rashīd al-Dīn Hamadāni, Jami’ al-tawārīkh, (Compendium of the Chronicles) (Morgan 2012) and the earlier chronicle by ‘Alā’ al-Din Juwaynī (Juwaynī, ‘Alā’ al-Dīn ‘Aṭa Malik 1912-37). The subsequent integration of Ilkhanid state dynastic control with Persianate language and influence in Persia, Tajikistan and parts of Afghanistan continued, while the Timurid branch that succeeded it absorbed Turkic speaking and Turkic language influence under Timurlane’s rule and succession that made Samarkand its capital.

To the East, the reign of Qubilai Kahn intersected with that of the impressive Song Dynasty (960-1279() which the Mongols replaced with the Yuan Dynasty from 1271 onward. Qubalai Khan integrated Confucian and Buddhist hierarchies and administration into his own dynastic rule and he gave his son both a Chinese Confucian and Buddhist based education as a process of enculturating the Mongols’ elite into Chinese. The Yuan Dynasty ruled in China from 1271 to 1368, when after a series of failed naval invasions against Japan, natural disasters, famine and failed harvests it was finally toppled and replaced by the Ming Dynasty.

Barthold, W. 1968. Turkestan down to the Mongol Invasion. Third Edition. Vol. V. London.

Bosworth, Edmund. 2010. The steppe peoples in the Islamic World. Vol. 3, in The New Cambridge History of Islam:, edited by David O. Morgan and Anthony Reid, 21-77. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cleaves, Francis W. ed. 1986. The Secret History of the Mongols. Translated by Francis W. Cleaves. Cambridge, MA.

Grousset, René. 1970. The empire of the steppes: A history of Central Asia. Translated by Naomi Walford. New Brunswick, N.J.

Juwaynī, ‘Alā’ al-Dīn ‘Aṭa Malik. 1912-37. Tārikh-i jahān-gushā. Edited by Mirzā Muḥammad Qazwīnī. Vol. XVI. 3 vols. Leiden.

Manz, Beatrice Forbes. 2010. The rule of the infidels: the Mongols and the Islamic World. Vol. 3, in The New Cambridge History of Islam: The Eastern Islamic World Eleventh to Eighteenth Centuries, edited by David O. Morgan and Anthony Reid, 128-168. New York: Cambridge University Press.

McChesney, R.D. 2010. “Islamic culture and the Chinggisid restoration: Central Asia in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.” In The New Cambridge History of Islam: The Eastern Islamic World Eleventh to Eighteenth Centuries, 239-265. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Morgan, D.O. 2012. Ras̲h̲īd al-Dīn Ṭabīb. Second Edition. Edited by Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs P. Bearman. New York: E.J. Brill. Accessed 4 2, 2017. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_6237.

Soucek, Svat. 2000. A history of Inner Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Subtleny, Maria E. 2010. “Tamerlane and his descendants: from paladins to patrons.” In The New Cambridge History of Islam: The Eastern Islamic World Eleventh to Eighteenth Centuries, 169-202. New York: Cambridge University Press.

[1] Beatrice Forbes Manz, “The rule of the infidels: the Mongols and the Islamic World,” in The New Cambridge History of Islam: The Eastern Islamic World Eleventh to Eighteenth Centuries, ed. David O. Morgan and Anthony Reid (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

[2] Ibid. p. 130-31.

[3] Ibid. p 133.

[4] Ibid. 137.

[5] Ibid. 142.

For a guide to the history of the Mongol Empire go to this website at Columbia University.

Silk

Roads / Mongol Empire From the Asia

for Educators website at

Columbia University:

Their main page is http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/special/silk_road.htm • The Silk Roads: An Educational Resource [Education About Asia, The Association for Asian Studies] This article by the City University of New York professor Morris Rossabi appeared in the Spring 1999 issue of Education About Asiamagazine. • The International Dunhuang Project: The Silk Road Online [The British Library] The International Dunhuang Project is "a ground-breaking international collaboration to make information and images of all manuscripts, paintings, textiles and artefacts from Dunhuang and archaeological sites of the Eastern Silk Road freely available on the Internet and to encourage their use through educational and research programs." This website is a truly comprehensive resource for teaching about the Silk Road. See especially the EDUCATION>TEACH section for teaching websites on various topics, including Buddhism on the Silk Roadand The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. Art of the Silk Road: Cultures: The Sui Dynasty [University of Washington, Simpson Center for the Humanities] The Travel Records of Chinese Pilgrims Faxian, Xuanzang, and Yijing: Sources for Cross-cultural Encounters between Ancient China and Ancient India [PDF] [Education About Asia, Association for Asian Studies] Article about three Chinese monks who traveled to India: Faxian (337?-422?), Xuanzang (600?-664), and Yijing (635-713). With maps. Reprinted with permission of the Association for Asian Studies. Lesson Plan + DBQs • Religions along the Silk Roads >> Xuanzang's Pilgrimage to India [PDF] [China Institute] Unit Q from the curriculum guide From Silk to Oil: Cross-cultural Connections along the Silk Roads, which provides a comprehensive view of the Silk Roads from the second century BCE to the contemporary period. In this lesson "students will travel with the pilgrim-monk Xuanzang (c. 596-664) and share some of the hardships of his journey. They will learn about religious pilgrimage from a Buddhist point of view." • Xuanzang: The Monk Who Brought Buddhism East [Asia Society] "The life and adventures of a Chinese monk who made a 17-year journey to bring Buddhist teachings from India to China. Xuanzang subsequently became a main character in the great Chinese epic Journey to the West." Mongol Empire (Yuan Dynasty) 1279-1368 CE Overview Maps • Dynasties of China [The Genographic Project: Atlas of the Human Journey, NationalGeographic.com] Printable Map • Maps of Chinese Dynasties: Yuan Dynasty [The Art of Asia, Minneapolis Institute of Arts] Interactive Map • Yuan Dynasty, 1260–1368 [Princeton University Art Museum] • The Mongol Dynasty [Asia Society] Background about "Kublai Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan • The Mongols in World History [Asia for Educators] The Mongols' Mark on Global History (International Trade, Pax Mongolica, Support of Artisans, Religious Tolerance The Mongol Conquests (What Led to the Conquests?, Chinggis Khan's Role, The Empire's Collapse, etc.); The Mongols in China (Khubilai Khan, Life in China under Mongol Rule, etc.); Key Figures in Mongol History (Chinggis Khan, Khubilai Khan, Ögödei, Marco Polo); and The Mongols' Pastoral-Nomadic Life Video Unit • The World Empire of the Mongols [Open Learning Initiative, Harvard Extension School] Lesson Plan + DBQs • Ethnic Relations and Political History along the Silk Roads >> China under Mongol Rule: The Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368) [PDF] [China Institute] From Silk to Oil: Cross-cultural Connections along the Silk Roads, which provides a comprehensive view of the Silk Roads from the second century BCE to the contemporary period. "This unit investigates why the Mongols can be considered the greatest conquerors in world history. Students will look at how the Mongol conquests changed the Eurasian world and discuss how Khubilai Khan (1215-1294) and his advisors ruled one of the greatest prizes won by Mongol armies: China." Marco Polo, 1254-1324 AFE Special Topic Guide • Marco Polo in China [Asia for Educators] A compilation of primary source readings, discussion questions, and lesson ideas intended to expose students to the impressive developments in Chinese civilization during the Yuan period.

Some Travelers of the Silk Route / after the Mongol Invasion:

Their main page is http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/special/silk_road.htm • The Silk Roads: An Educational Resource [Education About Asia, The Association for Asian Studies] This article by the City University of New York professor Morris Rossabi appeared in the Spring 1999 issue of Education About Asiamagazine. • The International Dunhuang Project: The Silk Road Online [The British Library] The International Dunhuang Project is "a ground-breaking international collaboration to make information and images of all manuscripts, paintings, textiles and artefacts from Dunhuang and archaeological sites of the Eastern Silk Road freely available on the Internet and to encourage their use through educational and research programs." This website is a truly comprehensive resource for teaching about the Silk Road. See especially the EDUCATION>TEACH section for teaching websites on various topics, including Buddhism on the Silk Roadand The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. Art of the Silk Road: Cultures: The Sui Dynasty [University of Washington, Simpson Center for the Humanities] The Travel Records of Chinese Pilgrims Faxian, Xuanzang, and Yijing: Sources for Cross-cultural Encounters between Ancient China and Ancient India [PDF] [Education About Asia, Association for Asian Studies] Article about three Chinese monks who traveled to India: Faxian (337?-422?), Xuanzang (600?-664), and Yijing (635-713). With maps. Reprinted with permission of the Association for Asian Studies. Lesson Plan + DBQs • Religions along the Silk Roads >> Xuanzang's Pilgrimage to India [PDF] [China Institute] Unit Q from the curriculum guide From Silk to Oil: Cross-cultural Connections along the Silk Roads, which provides a comprehensive view of the Silk Roads from the second century BCE to the contemporary period. In this lesson "students will travel with the pilgrim-monk Xuanzang (c. 596-664) and share some of the hardships of his journey. They will learn about religious pilgrimage from a Buddhist point of view." • Xuanzang: The Monk Who Brought Buddhism East [Asia Society] "The life and adventures of a Chinese monk who made a 17-year journey to bring Buddhist teachings from India to China. Xuanzang subsequently became a main character in the great Chinese epic Journey to the West." Mongol Empire (Yuan Dynasty) 1279-1368 CE Overview Maps • Dynasties of China [The Genographic Project: Atlas of the Human Journey, NationalGeographic.com] Printable Map • Maps of Chinese Dynasties: Yuan Dynasty [The Art of Asia, Minneapolis Institute of Arts] Interactive Map • Yuan Dynasty, 1260–1368 [Princeton University Art Museum] • The Mongol Dynasty [Asia Society] Background about "Kublai Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan • The Mongols in World History [Asia for Educators] The Mongols' Mark on Global History (International Trade, Pax Mongolica, Support of Artisans, Religious Tolerance The Mongol Conquests (What Led to the Conquests?, Chinggis Khan's Role, The Empire's Collapse, etc.); The Mongols in China (Khubilai Khan, Life in China under Mongol Rule, etc.); Key Figures in Mongol History (Chinggis Khan, Khubilai Khan, Ögödei, Marco Polo); and The Mongols' Pastoral-Nomadic Life Video Unit • The World Empire of the Mongols [Open Learning Initiative, Harvard Extension School] Lesson Plan + DBQs • Ethnic Relations and Political History along the Silk Roads >> China under Mongol Rule: The Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368) [PDF] [China Institute] From Silk to Oil: Cross-cultural Connections along the Silk Roads, which provides a comprehensive view of the Silk Roads from the second century BCE to the contemporary period. "This unit investigates why the Mongols can be considered the greatest conquerors in world history. Students will look at how the Mongol conquests changed the Eurasian world and discuss how Khubilai Khan (1215-1294) and his advisors ruled one of the greatest prizes won by Mongol armies: China." Marco Polo, 1254-1324 AFE Special Topic Guide • Marco Polo in China [Asia for Educators] A compilation of primary source readings, discussion questions, and lesson ideas intended to expose students to the impressive developments in Chinese civilization during the Yuan period.

Some Travelers of the Silk Route / after the Mongol Invasion:

Ibn Battuta 1325-1354 CE

Ibn

Battuta was born in Tangier (Morocco) in 1304 and was possibly the most widely

traveled individual until the era of modern exploration or the age of the steam

locomotive. As a trained

legal scholar, Ibn Battuta managed to work his way as a judge (qadi) around the main core cities and to

the periphery of the expansive Muslim world of the 14th century. His travel account the Rihla (Travel) is one

of the most famous travel accounts ever written and rivals Marco Polo's Travels as a seminal

text for understanding the late Middle Age system of trade and travel. After nearly thirty years of travels

across Africa, into Russia, Yemen, India, Southeast Asia, the Philippines and

China, Ibn Battuta returned to Tangier where he completed his book and finished

his career as a judge.

Along with Ibn Khaldun's Muqaddimah (Introduction to History) and his longer sets of historical writing, Ibn Battuta provides us with as complete a historical survey of the system of interchange and cooperation that existed across Islamic civilization during through the 14th century. As a survivor of the Black Plague, Ibn Battuta provides us with comparative material on the status and level of various cities and regions of this period.

Doubts about whether Ibn Battuta actually traveled to all of the locations described in his Rihla (Travels) have been raised by a number of historians. These historians particularly doubt his descriptions or ability to have traveled to the Volga River in Russia, or to parts of Yemen or the Pacific ocean islands of Southeastern Asia.

For summary excerpts from his Rihla go to http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/1354-ibnbattuta.html

Self-Study: An interactive map of Ibn Battuta's travels from his home in Morocco to China and back is available at: http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/200004/map/

Secondary Sources:

Ross E. Dunn, The Adventures of Ibn Battuta, A Muslim Traveler of the 14th Century (London: Croom Helm, 1986)

Along with Ibn Khaldun's Muqaddimah (Introduction to History) and his longer sets of historical writing, Ibn Battuta provides us with as complete a historical survey of the system of interchange and cooperation that existed across Islamic civilization during through the 14th century. As a survivor of the Black Plague, Ibn Battuta provides us with comparative material on the status and level of various cities and regions of this period.

Doubts about whether Ibn Battuta actually traveled to all of the locations described in his Rihla (Travels) have been raised by a number of historians. These historians particularly doubt his descriptions or ability to have traveled to the Volga River in Russia, or to parts of Yemen or the Pacific ocean islands of Southeastern Asia.

For summary excerpts from his Rihla go to http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/1354-ibnbattuta.html

Self-Study: An interactive map of Ibn Battuta's travels from his home in Morocco to China and back is available at: http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/200004/map/

Secondary Sources:

Ross E. Dunn, The Adventures of Ibn Battuta, A Muslim Traveler of the 14th Century (London: Croom Helm, 1986)

Ibn Khaldun writes a History of the World

Ibn

Khaldun (1332-1406) was a Tunisian scholar who traveled widely across the

Muslim world and wrote one of the most famous of all historical works, the Kitab al-Ibar, of which the

Introduction has been translated into English as The Muqaddimah.

Khaldun received an excellent education but was orphaned at the age of 16 when his parents and much of his family succumbed to the Black Death. He worked as an administrator and consultant in government at courts in Fez in Morocco and Granada in Spain. After a series of political intrigues that landed him into prison he withdrew from political life and began to study the social conditions of Berber and semi-nomadic peoples in the neighboring regions of the Sahara. He compiled regional histories and set out to develop a type of comparative history that also drew upon his own personal experience. Ibn Khaldun developed a theory about the rise and fall of dynasties and the importance of asabiya or group feeling or solidarity as a factor in sociology and history of power dynamics. Like Ibn Battuta he worked as a judge (qadi) in Cairo and famously met the conqueror Tamurlane as part of negotiations with the Mongol ruler and the Mamluks.

Exhibition website on Ibn Khaldun http://www.ibnjaldun.com/index.php?L=7

The BBC has an audio podcast on Ibn Khaldun's importance at http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00qckbw

An electronic version of Al-Muqaddimah or the Introduction to the Kitab Al-Ibar is at http://www.muslimphilosophy.com/ik/Muqaddimah/

Khaldun received an excellent education but was orphaned at the age of 16 when his parents and much of his family succumbed to the Black Death. He worked as an administrator and consultant in government at courts in Fez in Morocco and Granada in Spain. After a series of political intrigues that landed him into prison he withdrew from political life and began to study the social conditions of Berber and semi-nomadic peoples in the neighboring regions of the Sahara. He compiled regional histories and set out to develop a type of comparative history that also drew upon his own personal experience. Ibn Khaldun developed a theory about the rise and fall of dynasties and the importance of asabiya or group feeling or solidarity as a factor in sociology and history of power dynamics. Like Ibn Battuta he worked as a judge (qadi) in Cairo and famously met the conqueror Tamurlane as part of negotiations with the Mongol ruler and the Mamluks.

Exhibition website on Ibn Khaldun http://www.ibnjaldun.com/index.php?L=7

The BBC has an audio podcast on Ibn Khaldun's importance at http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00qckbw

An electronic version of Al-Muqaddimah or the Introduction to the Kitab Al-Ibar is at http://www.muslimphilosophy.com/ik/Muqaddimah/

No comments:

Post a Comment